[draft in progress]

Women are the dominant force in the micro industry cluster labeled by the Bureau of Labor Statistics as cultural events managers. The category includes staff positions from companies like Disney and places like Las Vegas, those professionals who run large public and private events on a routine basis. It includes positions like the White House Social Secretary who command sizable budgets and media attention and whose productions have national meaning, as well as contractors who produce neighborhood events like classes and workshops. This relatively small network of professionals is largely women, which makes it an interesting one to study from the lens of leadership.

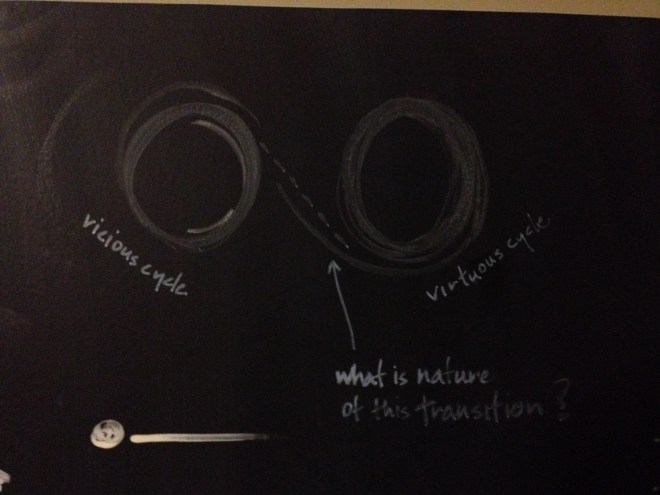

Theories of leadership have been in development since ancient philosophy and are present in all world civilizations. A lineage of leadership theory (largely Western in origin) has been mapped out in progressive stages, with us approaching an important point of integration. We know enough about leadership now to understand that it comes in multiple forms, is place and time dependent, and requires a diversity of perspective to operate at a social level.

It is typical and routine for a creative profession to be at the forefront of change in leadership style. By definition, creative work requires the practitioner to take hold of the future. She produces events and experiences that happen there (event planning is a thing) and designs the style and message of the event, which have inherently cultural implications always.

The practice of integrative leadership is more common among cultural events managers than it is in other labor groups. There are structural reasons for that, including the functional necessity of teams in event production, multiplicities of resource allocations, and the evolution of technologies that allow for more complex productions. The specific correlations for class and gender matter too. A dominant combination of women and working class people on a team is more likely to produce an integrative leadership style. Teams are central to event production, and integrative leadership is central to team-based productivity.

It wasn’t always so and even recent organizational leadership theory attempts to retain a formal, charismatic leader as the inspiration and engine of a team. He stands at the front of a room, presumes to know a plan, directs others’ work, and is ultimately held accountable for team performance. That may still be the organizational mandate most cultural events managers toil under, but that’s not how they work.

Rooted in traditions older than leadership theory, women and working people have ways of accomplishing meaningful action together. These leadership styles (and their aims, strategies and methods) are better understood through the lens of family, friendship, and community than they are through modern organizational theory. How young leaders learn these traits and habits (at home and in civic spaces) is a topic for another post. For now, we can safely assume that they know what they’re doing.

So what can this tiny, nearly invisible class of industrial professionals tell us about leadership right now? Let’s ask them.

[draft in progress]