Today, I joined 250+ virtual participants in a national convening on the future of American arts and culture. Organized by a few humble leaders and attended by a critical mass of people from across the arts ecosystem—artists, funders, researchers, policy professionals, and advocacy leaders—we addressed central questions on the prompt: What should the arts and cultural sector look like in 2045?

Creative Bones in Our Bodies

Maria pulls out the shoebox at her daughter’s kitchen table. Inside: forty postcards from her grandmother’s trip to Havana in 1957, three from her own honeymoon in San Francisco, a dozen her children sent from summer camp. She tells the story of each one to the family history circle that meets monthly online—how her abuela’s handwriting changed after the stroke, why her son drew a cat on every postcard from Wisconsin. The facilitator doesn’t call this “arts programming.” It was actually recommended as grief counseling. Maria doesn’t care what you call it. It helps.

David discovers watercolor tutorials on YouTube at 3 AM in his hospital bed. Chronic pain keeps him awake most nights. His occupational therapist mentioned it might help, so he watches a British woman explain wet-on-wet technique on his phone. By morning rounds, he’s painted seven terrible trees. His nurse asks if he’s an artist. He laughs, “I’m an accountant.” Something in his nervous system has shifted. The pain is still there, but he feels better.

Uncle Luis is a traveling musician who never misses his weekly video chat with Tyler in Houston. Tyler is thirteen, wants to be in a band, but struggles with relating to his friends at school. Luis grabs his acoustic guitar propped on the wall of his Madrid hotel room and shows Tyler three new chords. They’ll never perform together. There’s no recital, no teacher, no institution involved. Just a kid and his uncle, one teaching the other something he loves. Tyler is learning by ear, the same way humans always have. Luis worries, “Well, maybe it’s not the same at all.”

None of them (except Luis) would say they’re participating in “the arts.” But they are experiencing what we advocate for: creative practice as connection, healing, the experience of joy, and the transmission of cultures. In fact, society is awash in these new creative connections, and also deeply burdened by what they mean for the pathways forward.

Here’s the crux of our “arts” problem as I see it. We have consistently defined and defended a tiny institutional footprint while the lived experience of the arts is everywhere. We measure attendance figures and economic multipliers while the actual transformations are self-evident and they happen in kitchens, hospitals, and video calls.

Joy is our true unit of exchange, and it has always been non-fungible. This is not to say joy doesn’t produce great economic prosperity. In fact, not much can be truly valued without it. Joy has wonderful exponential properties, too. Watch it grow in a family, neighborhood, or community and behold the influential power that comes from joy over time.

The opportunity cost of our narrow focus? Enormous. While we fight for NEA crumbs, healthcare systems spend trillions. While we justify arts education, again, employers desperately need creative capacity and are willing to invest. While we protect nonprofit institutions, commercial creative industries from Palo Alto to Atlanta wield massive global power with little accountability to our American values. We’re playing a very small game in an outdated arena when the importance and impact we describe is everywhere.

Three mindset shifts are available to us now.

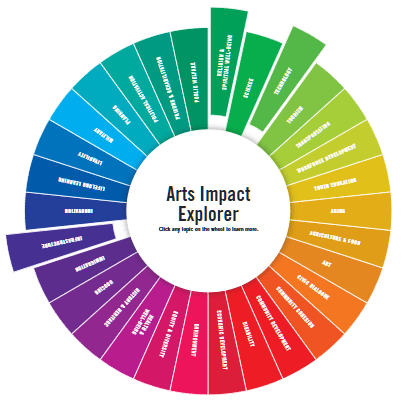

First, recognize the full ecosystem. Creative practice happens primarily in relationships—families, friendships, communities. Commercial creative industries drive economic and diplomatic power. Nonprofits serve specific functions within something much larger. Stop conflating one part with the whole. Walk and chew gum on a global scale.

Second, flip from defense to offense. Stop justifying institutional existence. Start connecting city leaders to the creative capacities flourishing in their communities and the commercial powerhouses in their regions. Position all of it—relational practice, industry strength, institutional programs—as strategic assets for tourism, economic development, and global influence. Back your mayor, or work to get a new one.

Third, meet people where they are. Partner with healthcare systems integrating creative practice for brain health. Support schools, community centers, and veterans homes as creative practice hubs. The pathway to universal participation runs through these everyday institutions—through neuroscience, public health, youth development, elder care—not arts funding policy alone.

This approach is appreciative: it recognizes what’s already working. It builds on strengths and follows universal design principles as found in archetypes, stories from all cultures, and nature. It rests in accordance with sacred cycles, and is still always moving.

It’s emergent: the future arises from millions of small acts. Our professional roles are to remove barriers and create conditions where what is flourishing can ripple out. We don’t need to convince people creativity matters. We are neurologically wired to have those desires and seek their expressions. Our powers and practices are ancient.

It’s integrative: we weave together what’s been artificially separated. Creative practice is found in preventive healthcare, workforce development, community resilience, climate conservation, cultural diplomacy, and economic strategy. When we connect across sectors, we tap resources far beyond what arts funding policy can marshal.

By 2045, creative practice must be regarded as an American birthright in which everyone has skills, confidence, and community to pursue happiness, to make their lives joyful and meaningful. In two decades time, the opportunities of American cultural life will again be the reason international visitors flock to our parks, and immigrants continue to seek their futures here with us.

This requires honest reckoning. The institutional arts sector was built through exclusion—who got to make art, whose art got valorized, who had access, who made decisions. As we attempt the experiment again, we can become less perfect and more ourselves. All of us.

The democracy our children need is one where every person participates in making culture. Where creative capacity is distributed as widely as literacy. Where expressing yourself and connecting across difference is as fundamental as reading and writing, and is its own kind of fluency.

Maria, David, and Tyler don’t need us to advocate for them. They’re already doing it. They need us to stop pretending institutions tell the whole story. They need us to build policy around creative practice as a human birthright. It’s already everywhere, and our job is to prepare, promote, and protect the conditions in which joyful, creative lives naturally flourishes in every American community.

I cherish my years in DC arts policy before becoming a caregiver, a writer, and a social entrepreneur. The Posted Past is a social enterprise trading loneliness for connection, one postcards at a time. I’ve seen firsthand that person-to-person work creates more of the connections we need over time. Of course, we need policy, funding, infrastructures, marketplace strategies, and legal heft. We also need to exemplify cultural leadership with integrity in our families, at work and school, on the corner, down the block, and along the way.

Talking Points for the Wonks in the Room

1. RECOGNIZE THE OPPORTUNITY COST

“We’re defending institutional territory while leaving trillions on the table. Healthcare systems are integrating creative practice for brain health. Employers need creative capacity. Commercial industries from LA to Atlanta wield global influence. The opportunity cost of our narrow focus is enormous.

Where we’re coming from: Decades of defensive advocacy focused on protecting NEA funding and justifying institutional existence through impact metrics and economic studies.

Where we’re going: Strategic positioning of American creative capacity—all of it—as a force for global tourism, economic development, brain health, and cultural diplomacy. We tap into trillion-dollar healthcare, wellness, and economic development systems.

The opportunity: When we connect creative practice to sectors where massive resources already flow, we expand impact exponentially while strengthening the case for institutional support as one piece of a much larger ecosystem.

2. THE ECOSYSTEM IS BIGGER THAN INSTITUTIONS

“Creative practice happens everywhere through relationships—families, communities, in parks, at work, and through informal networks. Our policy problem is we’ve conflated nonprofit institutions with the arts themselves.”

Where we’re coming from: Policy frameworks that center institutional access and treat creative practice as something that happens exclusively by artists in designated cultural spaces with professional mediation.

Where we’re going: Recognition that creative practice is primarily relational and already flourishing everywhere. Our role is to remove barriers and create conditions for what’s working to spread—through schools, community centers, healthcare settings, and informal networks.

The opportunity: When we stop defending a narrow definition of “the arts,” we gain millions of allies already doing this work in education, healthcare, community development, and family life. We become relevant to how people actually live.

3. MEET PEOPLE WHERE ADOPTION ENERGY EXISTS

“The next wave of creative practice adoption is coming through healthcare, schools, workplaces, community centers, and veterans homes. These are trillion-dollar systems already integrating creative practice. Our job is to connect and lead in those spaces.”

Where we’re coming from: Trying to convince people that creativity matters, arguing for arts education mandates, seeking cultural policy solutions for narrow slices of the creative sector.

Where we’re going: Partnering with systems where people are already choosing creative practice for brain health, workforce development, chronic disease management, youth development, and elder care. We are at the leading edge of what’s working in each of those spaces.

The opportunity: Healthcare, education, and economic development sectors have resources, infrastructure, and urgency we lack. By positioning creative practice as essential to their missions, we achieve a scale and influence impossible through arts funding policy alone.