I play word games throughout my day in pursuit of lyrical miracles. As a writer and lover of spoken word, I spin puns for fun. Words weave our wisdom stories, too. Like my friend who faced both hell and high water and sends a haiku every Thursday.

I invent phrases, too. Usually for a functional purpose, and most often in a fit of laughter. Shame I’m not quoted more often ;) Or am I?

Recently, I was challenged by the latest work from a beloved colleague making good trouble out of a phrase we invented together. #ArtsManaged

It’s the hunch that this moment is both spontaneous and aligned. As though it was meticulously planned by professional teams tending to all the things. Elegant and efficient. Bubbly effervescence bound by boxcutter utilitarianism. Polite and pragmatic. Often planned chaos.

When you leave the gallery, theatre, park, or public square wondering, how did they do that? You’ve been #ArtsManaged.

In our time at AU, students in Ximena’s class invented “all the things” as a concept, and it has flourished through arts management networks. Sherburne often had us in belly laughs and always ended up with a check. Andrew advanced ideas in the moment — sometimes in song — a generous thinking out loud we all enjoyed.

#ArtsManaged was invented at a faculty meeting, along with hilarious insider lingo. We riffed on all manner of AU brand business and how it could further bond our kickass students and beloved pro network. I left feeling cosmically on point.

Then, I was excused from service at AU, and there were uncomfortable years when we didn’t speak.

I love the moment and the memory no less. But I was uninvited to the party when I separated from the university. My connections to colleagues were severed, and also my part in the invention. Somehow, that moment wasn’t a part of my story anymore, or at least it wasn’t pleasant to remember.

Now lately, Andrew has taken the phrase #ArtsManaged to a new place on his esteemed blog. He does the blog with his not-spare-at-all time and heaps of professional integrity.

Pride and sadness mingled again at the announcement, though.

My claim on the phrase has nothing to do with intellectual property, and I resist capitalist tendencies that try to own community work. Lovely folks produce artistic work collectively all the time. The efforts are sometimes intentionally unrecognized for the greater good. An economy of friendly favors undergirds nearly all creative work. We eagerly monetize it too often.

Rather, I felt a heart ping back to that moment and the #ArtsManaged story as part of my trajectory, too.

I play strong in early stages and generative spaces, where merrily mixing it up is method. Get some laughter lit among good people. Let the language loose. Leave bits laying around like tinsel after an epic night. Found phrases to pick up, pack away, and pull out on another day. Music playing. Swaying, too. Mingling and tingling among all those neural fireworks.

It’s all good fun until someone authors the phrase.

Words get written down. A style is applied, and a meme is created. It’s both fair copyright and a socially good outcome. The phrase is alive and working in the world. Huzzah.

But the origin story is flattened in a deleterious way, too. The collective efforts of the creative studio become invisible as they enter the classroom, office, marketplace, and polis. A happy/sad memory for those who were present, and a subtle misrepresentation of creative practice. One that leans toward stereotypes of solo genius and sometimes forgets collective work.

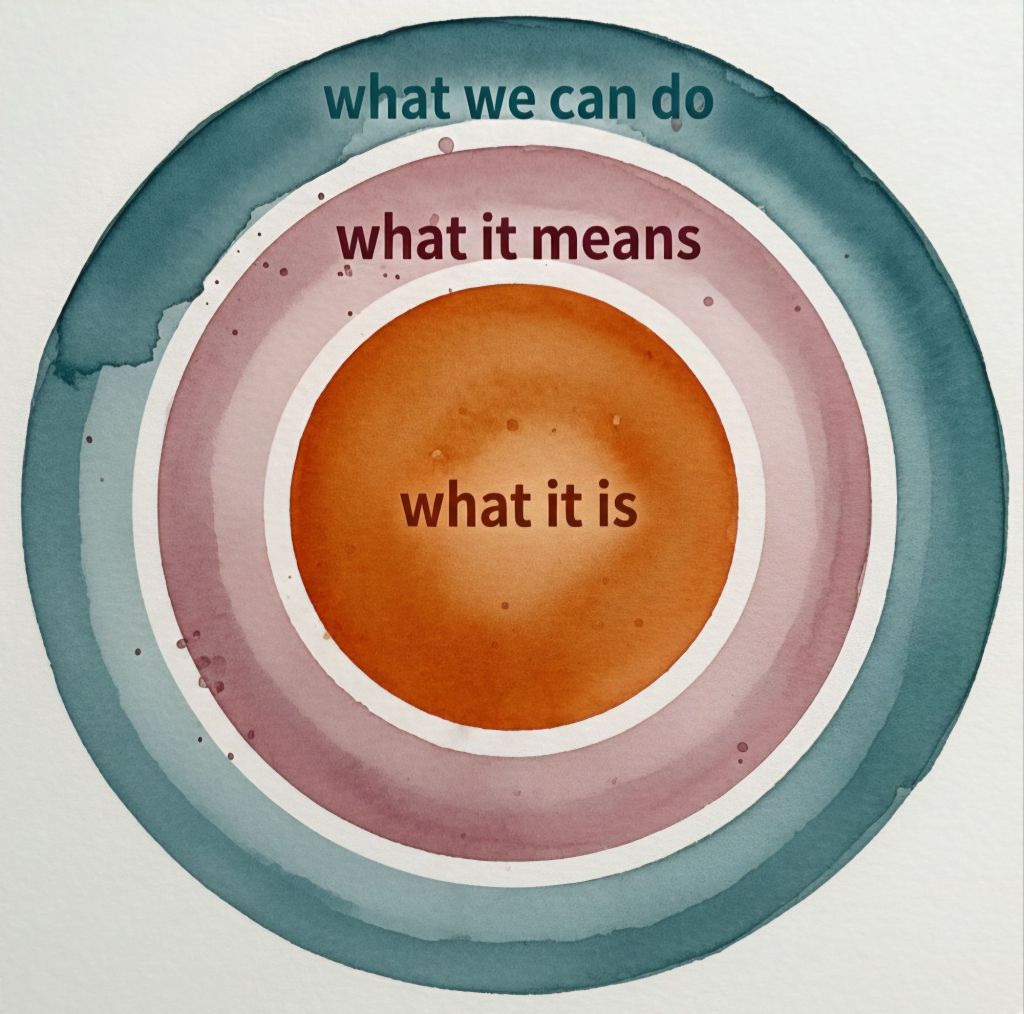

Primarily, arts management is a practice. Like the art itself, it only matters if it happens. Yes, theories and evidence inform our work. But those are the maps, not the terrain.

A legendary leader once described us creatives as eternally restless. We have more than a simple tolerance for ambiguity. We actually love the people and places way off the map.

I used to run to my desk to start work each day. I believed I belonged to a grandly diverse tribe intent to unite the world in peace through arts and cultures. Naive, I know. But as mental maps go, simple serves me.

I leaned into creative practice when working on policy in DC, too. Trained in graphic design, visually inclined, and inspired by Edward Tufte, my years on the arts research desk produced early wireframes for what is now newly-minted federal arts policy.

Different from some truly skewed theories popular at the time, I sought out evidence of what was actually happening in society through the arts. I looked for genuine social impact in American communities. Not just the statistics we thought would raise money, but the practical charts, infographics, summaries, one-pagers that illustrated our larger purpose and function. My research showed the centrality of the arts to civic life and the integrative ways we operate in neighborhoods. The arts are uniquely positioned to cause ripple effects in society.

For most of my career, my writing has been intentionally quiet. I write policy proposals, funding justifications, and speeches for other people. Still, my exact phrases — words I strung together decades ago — persist on some prominent websites. I smiled quietly in my last job when I was briefed on my own work, uncited. One of the thrills of exchanging recognition for influence.

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi made famous the realities of Flow. We know from Chaos Theory that our cultural restlessness perpetually alternates between structure and ambiguity. Like all humane development, we start in a soupy muck of information and inference, only sometimes informed by intelligence and insight. Turns out, a Comic Self may come in handy. More recently, books like Braiding Sweetgrass remind us that certain cyclical flows reflect ancient wisdoms embodied in nature.

Cultural growth is rhizomatic, following the organics of people and place far more often than urban planners care to know. Culture eats strategy for breakfast, Peter Drucker famously said. For me, it’s always both/and. Strategies within organic contexts are wiser, kinder, and better devised when we understand Why.

Gardening is inherently hopeful, though the results can be merciless. At the moment, we seem to be heliotropics in hell. There is so much to make of these ambiguous times, but social change is at a boiling point and leaders are more than stressed. It is a counter-cyclical moment when former framers ought to rest.

I’m inspired to try and fail at a slower pace, too. That’s why I wrote to Andrew from a vulnerable place with a case for enduring cameraderie. Of course, he responded in empathy.

Through a brief email exchange, we noticed where our memories of time at AU joined up and didn’t. We affirmed a mutual commitment to problem-solving on behalf of the arts management field, especially when it’s hard. He wrote this companion post.

The creative work we do together takes time to grow. A symbolic seed planted years ago is sprouting now. Rhetorical roots have taken in policy and practice. We are far more fertile a field today.

Cheers for collaborative leadership in quiet places and spectacular scenes. And, here’s to the generations of creative leaders in between.

May we all be so #ArtsManaged.